-

Ken Matsubara

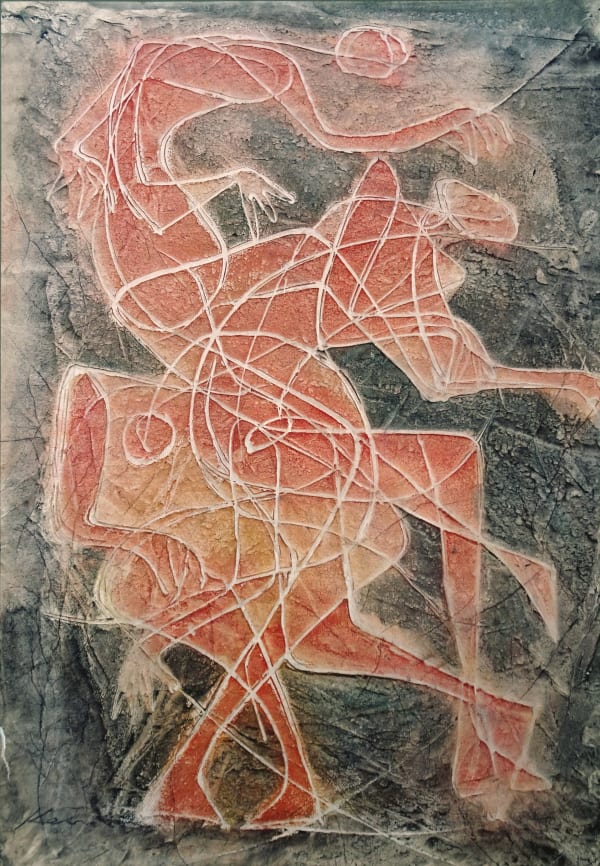

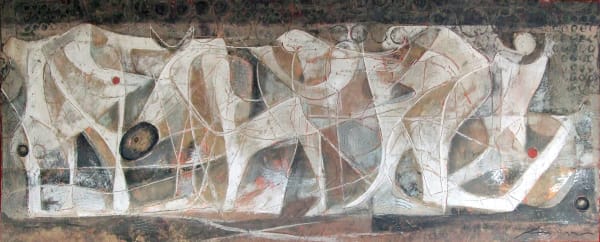

Chaos - 屏風「カオス」, 1983Painting

H70 7/8 x W433 1/8 in

H180 x W1100 cm -

An Essay by Ken Matsubara

When creating the paintings for the walls and partitions of the priest’s quarters at Jingoji Temple, I felt driven to experience the same scenery that the priest Kukai saw while striving for enlightenment. So I traveled to Cape Muroto, where he had lived. In the light of the false dawn before sunrise, the entrance to the Mikurodo cave appeared as a black void. I drove down to the end of the peninsula, where I saw the full moon shining over Tosa Bay, creating a pathway of light across the ocean. Having watched the moo disappear into the water at the end of this path, I returned to the Nikurodo cave as the eastern sky began to brighten. Two caves are standing next to each other, and the other one is called Shinmeikutsu. It is not a very deep cave, but it was here that Mao (Kukai’s childhood name) underwent an ascetic training known as kokuzogumonjiho. This consisted of chanting the true name of the Koku Bodhisattva one million times, thereby imbuing the practitioner with a super-memory that would make it possible to memorize any sutra after a single reading. The view from the mouth of the cave was rather monotonous, consisting solely of the sea and sky. However, like a cinema screen, the clouds gradually became tinted with gold and heralded the approach of dawn as the sun rose out of the sea directly in front of me. Bright rays of sunlight shone into the depths of the cave, and I felt enshrouded by light.

One thousand two hundred years ago, a young priest sat in the very same spot, chanting the name of the Kukū Bodhisattva. I stood dumbfounded as. I watched the morning sky and sea. In the evening, the moon rose out of the sea, slightly to the left of the place when the sun had risen. Compared to the Shinmeikutsu cave, the Mikurodo, which has served as his home, is situated at a better angle for this view.

In contrast to the dark entrance to the cave, the night sky was bright. Eventually, the moon moved out of the angle of view, and a myriad of stars began to travel slowly across the night sky. I felt that I could almost see the young priest sitting beneath this heavenly show, becoming one with the natural cycle of night and day, chanting the mantra and experiencing inner and outer space as he floated within the world of the mandala. Then, as he reached the fulfillment of this vow, he underwent a paranormal experience when a bright star flew into his mouth, and his spirit entered the abstract world. The young priest thus became “Kukai.”

- Ken Matsubara

-

Seigō Matsuoka

I was more than surprised to see the theme of the Niga Byakudō [White Path to Paradise between Two Rivers of Worldly Vice] treated in this manner…I was dumbfounded. When I first saw it, I felt dizzy with bewilderment. The artist, no doubt, hoped for this manifestation as he painted it, but I think that the awesome power that it transmits to the viewer surpasses even the artist’s intention. I was amazed, staggered, and forced to take my hat off to him.

In the place where the fires of purgatory clash with the surging waves of a river deep inside the artist, a white road appears. The Chinese master of Pure Land Buddhism, Shandao, used the parable of a white path that passes between two rivers and leads to paradise as a way of teaching the Pure Land beliefs, which later became the motif for numerous Buddhist paintings. Shandao stated that between the “impure world of this life” (here) and the “pure world of nirvana” (there), runs a white road that people must pass across; however, in many Buddhist paintings, this journey is depicted as a static composition. I have seen more than ten examples, all presenting the same image.

Yet in contrast, Ken Matsubara boldly expresses the Niga Byakudō through a conflict of the soul. Abstract and representational are interposed, concept and painting technique meld, Amida Buddha and Kannon/Seishi Bodhisattva create a circle, while human figures struggle to escape from chaos. All of this appears to be occurring in “the here and now.”

This is a work that can be displayed in any environment, whether it be as a Buddhist painting and a work of contemporary art, and it is sure to transport the viewer from “here” to “there.” It is how visions should manifest--how it should be.

Seigō Matsuoka

Director,

Editorial Engineering Laboratory Co. Ltd.

Director

Kadokawa Culture Museum

-

Chaos Video

by Ken MatsubaraView one of Ken Matsubara's long works of art. It ranges from hues of brilliant fire reds to deep earthy browns and rusty blacks. His work is powerful yet approachable, elegant yet pensive. Experience the one-minute-long clip that captures such a range of emotions.

-

Artworks

-

An Essay by Shoko Aono

The echo of the wind, the sound of water, a full moon floating in a mysterious blue sky, the cries of wild beasts that agitate the ripples of the lake…Ken Matsubara’s works present a view of the universe that is magnificent beyond description. For him, the act of drawing is to resonate with nature itself.

Prior to exhibiting his “Scenery” series in New York in 2014, he took a helicopter flight that allowed him to look down on Mt. Fuji. In that moment, he realized, “although mountains are formed from the earth, it is water that sculpts them,” leading him to use flowing water as paint in the showcase.

Later, in 2019, the highlight of this gallery’s grand openingwas his magnificent series, “Kūkai.” Those who attended found themselves drawn in by the roar of the sea and the mysterious profundity of the sun and moon. The current exhibition will be his third in New York and will feature a series of work that he first showed half a century ago.

In 1975, he was twenty-seven years old and enjoyed a period of concentrated study under Sankō Inoue. Inoue once said, “It is nothing. If you are not ordinarily healthy, you will never be truly moved.” Matsubara took these words to heart after Inoue’s death, devoting himself body and soul to create the Chaos (1983) painting that is featured here.

Chaos is Matsubara’s interpretation of a Buddhist painting entitled Niga Byakudō-zu [White Path to Paradise between Two Rivers of Worldly Vice], that he first saw at Zendōji temple in Gifu Prefecture when he was nine years old, and which had remained firmly etched upon his memory. In order to find the white road, it is necessary to possess a pure heart and cast aside the sediment of life that has built up inside one’s soul, otherwise it will be impossible to pass along this narrow white road that runs between the river of water, (attachments and greed) and the river of fire (anger and hatred). It was with this in mind that he confronted the twelve panels that comprise this work, a masterpiece through which he prayed for tranquility and purged himself of all the chaos that had accumulated within him. Like Picasso’s Guernica, it presents a tempestuous maelstrom of emotions and raging flames, but in between these, an indistinct, cloud-like, pure, white road emerges.

His later works are filled with a quiet, peaceful atmosphere. One characteristic theme of his works is “sound” which is expressed through a round motif. They possess an exquisite vibration that becomes as one with the cosmos, expressing the healthy spirit that Matsubara craves and which plucks at the viewer’s heartstrings.

Over the last fifty years, Matsubara has confronted the various events that have occurred to him with sincerity, faithful to all he meets, while continuing to express himself on white paper. “The fate of my works is definitely affected by people’s encounters with them.” Perhaps Matsubara’s white road will continue without end.