Kohei Nakamura, Kohiki Tea Bowl, 2022, (C24290)

If you visited the exhibition “Studio Craft Movement” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2007, you may have seen a ceramic by Nakamura Kōhei. Titled “Resurrection,” the highly ornate glazed porcelain piece resembles an elaborate Baroque mantle clock. It seems hard to believe that it is the same artist who crafted the Kohiki Tea Bowl now on view at Ippodo Gallery, New York.

But just as the historical spectrum of Japanese art encompasses the architecture of both Nikko and Katsura, Nakamura’s creative reach embraces both the Baroque and the wabi esthetic of tea.

Nakamura Kōhei, born in Kanazawa in 1948, grew up in a family of potters and was exposed to ceramic arts from childhood. He attended Tama Art University, graduating from the Sculpture Department. This may account for Nakamura’s experimentation with the ornate, decorative style of pieces such as the one at the MMA. His foray into making tea bowls began with homage pieces, utsushi, of famous examples such as the red Raku bowl, “Kaga Kōetsu” by Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558-1637). Utsushi is often translated as “replica,” but Nakamura is not intending to make an exact copy, but rather, to pay homage to the originals as inspiration for new creations. By approximating the process by which the earlier tea bowl was made, the contemporary artist finds his own interpretation through working the clay. As the famed 17th-century haiku master Matsuo Bashō put it,

“I do not seek to follow in the footsteps of men of old; I seek the things they sought.”

With this “Kohiki Tea Bowl” Nakamura Kōhei brings his singular interpretation to the tradition of 16th-century Korean buncheong wares. Employing traditional methods, Nakamura formed the iron-rich clay into a bowl on a wheel, then dipped the piece into a white clay slip for the coloring before applying a clear glaze and firing it. The finished bowl does indeed evoke the images of its predecessors in its irregular shape and the “rough” look of the body and foot. And yet… What intrigued me immediately about Nakamura’s tea bowl was the “tear” in the lip rim. I don’t believe a Korean potter would have left this “flaw” even if he was intending the piece for use as a rice bowl. It seems Nakamura is challenging the would-be tea drinker to stop and look and think. Holding the bowl in my hand I can appreciate its shape, texture, and weight, as I would with other tea bowls. But with his subtle reinterpretation of the rim, Nakamura refocuses my attention to the sculptural aspect, to the hand of the potter and his individualistic “variation on the theme” of a traditional tea bowl. With this additional layer of creativity Nakamura has enhanced not only the aesthetic appreciation of the tea bowl, but the very process of using the bowl to enjoy a cup of matcha.

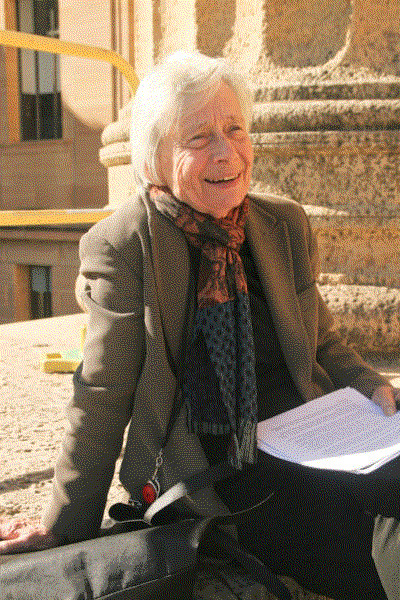

Felice Fischer

Curator Emerita of Japanese and East Asian Art

Philadelphia Museum of Art

2023