Ikuro Yagi: Grand Nature, the artist's debut exhibtion in the United States will conclude on November 22, 2024. We spoke to Yagi again about his artworks and reflections from his time visiting New York City to open the exhibition. His answers include new perspectives on teaching, how he sees the field of ink painting in Japan and overseas, and inspirations that stir future plans. The following transcript is a translation from the original Japanese.

Question 1: Classic Nihonga mediums—Sumi, iwa-enogu, nikawa, washi paper, and more—are on display in Yagi-sensei’s paintings. Yagi-sensei, please tell us a bit about the methods you apply to the mediums. Do you use brushes, or other tools? Please speak a bit more about ‘black leaf’ which is not well known in the world of art and how you’ve used it in these paintings.

Ikuro Yagi:

Sumi ink, which was born in China, has undergone a transformation in Japan. However, the tradition as a form of painting that could be carried on in China and Japan has long since disappeared. In China, it died out by the Northern Song and Southern Song dynasties, and in Japan by the Edo period. This is probably because of the individuality and understanding of each person. It may be because it was originally difficult to inherit.

Some people might say, “No, no, there are plenty of such things in Japan and China up to the present day, there are plenty of ink paintings in Japan and China,” but only a few vulgar ones have been handed down in a skeleton form, such as those in universities.

The truth is that drawing with ink as a form of expression has been almost completely denied.

I have been thinking about sumi ink since I was young. It seems easy to express with emotion, in ways that are gentle and strong, yet profoundly deep. Now, after 50 years, it finally became interesting to me. Sumi ink is used in my early collage works, but it is an expression of sensual air.

Mineral pigment paints and Japanese paper have been produced in large quantities since the 1920s as materials for painting, and after World War II, many amateurs began to paint with them. Inexpensive mineral paints, especially those made with chemicals, are now available and in use.

I use natural mineral pigments and natural barkless linen washi paper.

Black foil is made by oxidizing the surface of silver and baking it with sulfur and other mediums. However, there are now commercially available products and liquid oxidizing solutions, so it is not a particularly difficult technique.

Gold, silver, copper, aluminum, and other types of foil are available, but my works are mainly made of gold leaf and gold powder. They are used for spatial effect and as a pigment color. They were originally used for decoration.

Recycling is an expression that Japanese people have valued for a long time, and they have been using it in different ways, for example, by patching parts of clothes or using old house posts for different purposes. My collage is also a new expression of what used to be a way of restoring shoji screens by pasting different paper over them when the paper was torn.

Old is not necessarily better, but when an original idea is infused into the work, it can be revitalized and revived.

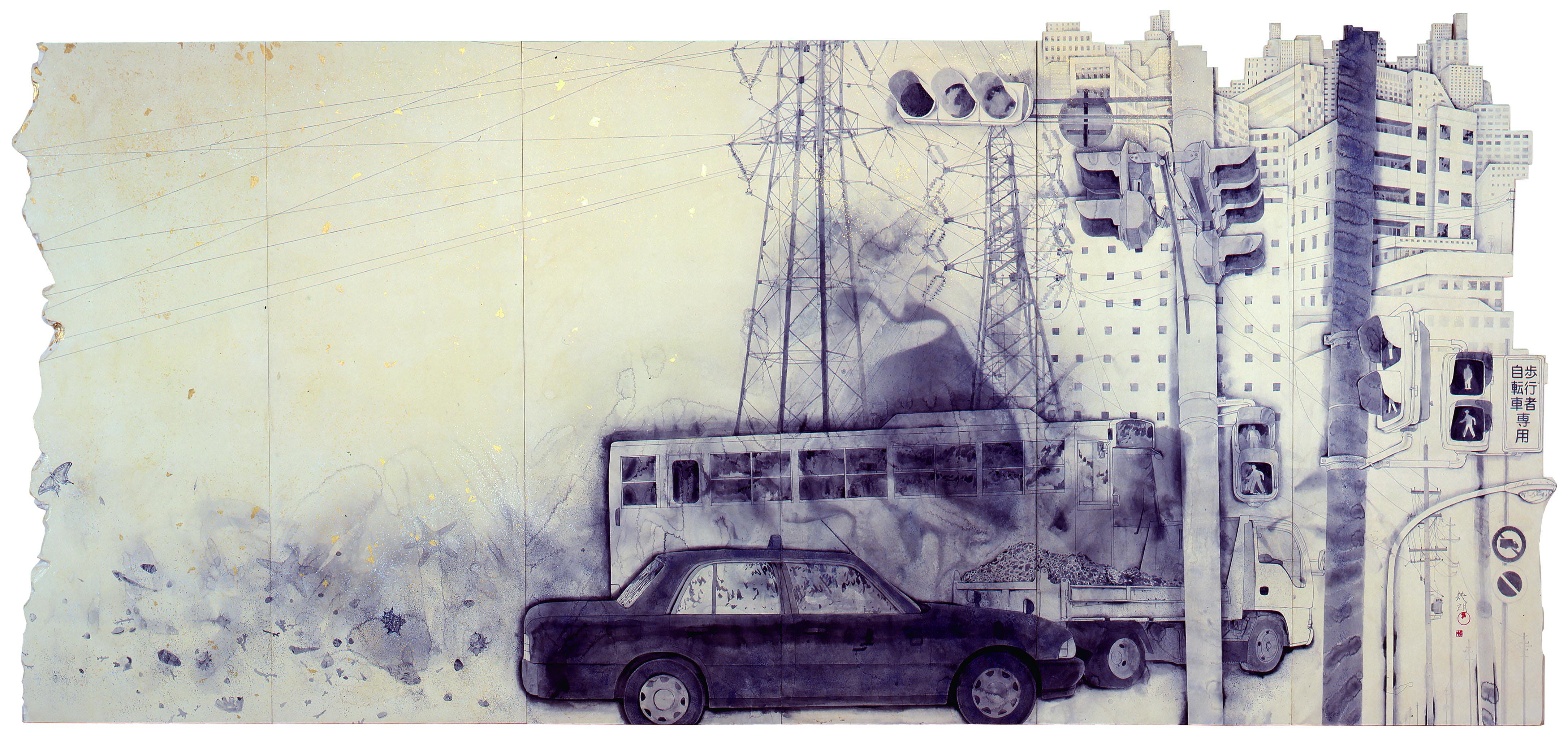

Q2: Found or recycled wood and other types of objects (such as rail-ties) are a unique facet of Yagi-sensei’s paintings; please explain the ideas behind these choices and about the power of painting in this way. When Yagi-sensei does work on paper, the form of the painting is not always uniform (e.x. Grape and Pheasant; La Ville). Please speak about why you make the choice to allow the picture to expand beyond a ‘regular’ frame.

Yagi:

For the past 20 years, I have been trying to create ink paintings in a form that no one has expressed before. This is not something that I set out to do, but it came naturally to me.

My mother was an oshie artist (a craftsman who produced Hakoita toys and other handicrafts that flourished during the Edo period), so I grew up seeing her semi-3-dimensional works from my childhood. I adopted her techniques and ideas without realizing it, and there is no other work in the world with a free-curved support made of Japanese paper.

Original ideas are an important element of art outside of Asia, where it is standard to copy. I felt this as a matter of course when I was in Paris.

I would like to know what people in New York think of what I have created over decades. It is the city of freedom.

Many of my paintings are large. It is a mural, a space that embraces the viewer. The Sistine Chapel, Horyuji Temple, Yakushiji Temple, the sea, mountains, and forests emphasize the smallness of human beings. It was with this in mind that I decided to paint large scenes.

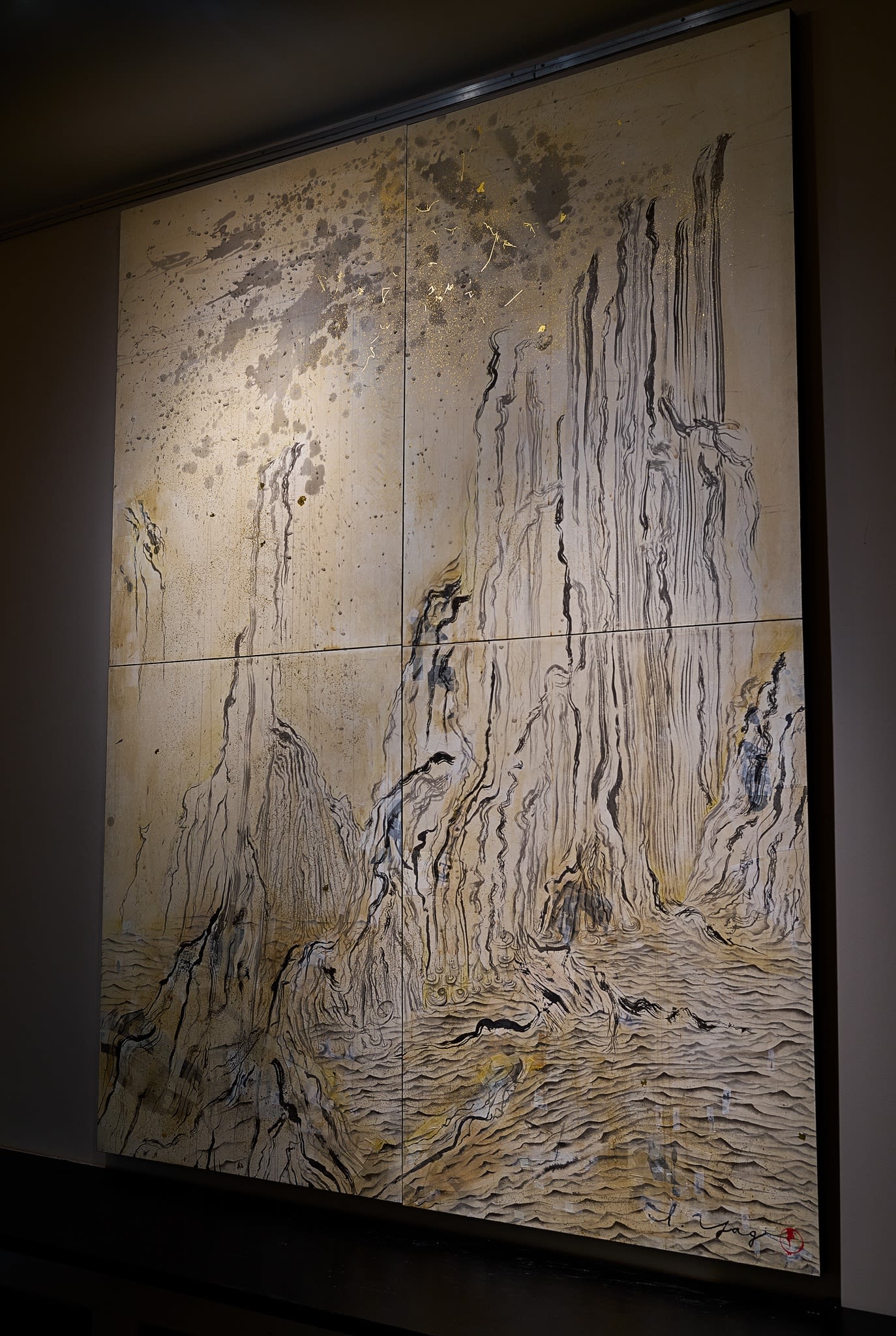

Q3: Collage is a staple in Yagi-sensei’s oeuvre. “Nature” is sensei’s latest work that draws on the same ideas from Mori-no-Kanata made 40 years prior. Both works will show in New York together; please speak about what your thoughts on nature; what connects these two artworks? Darkness features heavily. What is the power of darkness, and how has darkness changed, in Yagi-sensei’s mind, over the past 40 years?

Yagi:

I have created many collage works from 1980 to the present (2024). Although collage is a form of art, it may be closer to indigenous techniques such as shoji paper cut-and-paste and papier-mâché, rather than the compositional European expressions of Picasso and others. Of course, apart from these divergences, I think the different spaces, the flow of time, and the composition are intricately intertwined and give depth to the work. All of this is beauty that can be felt by the viewer and left to linger after the experience.

The black areas of the new work are painted in cashew lacquer and sumi, but the entire work is the deep dark space of a forest at night. Nature sometimes turns on humans violently. The Japanese paper part looks like the moon, waves, wind, and trees. Japan is a country of many disasters: earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcano eruptions happen one after another. Each time, Japan was supported and recovered by the relief and warm feelings from all over the world. For example, the support of the U.S. military during the Tohoku earthquake is unforgettable.

In this work, I hope to express the contrast of severity and kindness.

Human beings cannot live alone.

The darkness has changed over the past 40 years. I feel that the expression has changed to be more realistic due to the many disasters that have occurred in recent years.

Maybe it’s the feeling of intensity that comes from a quiet forest. I think I’d like to paint a universal view once again.

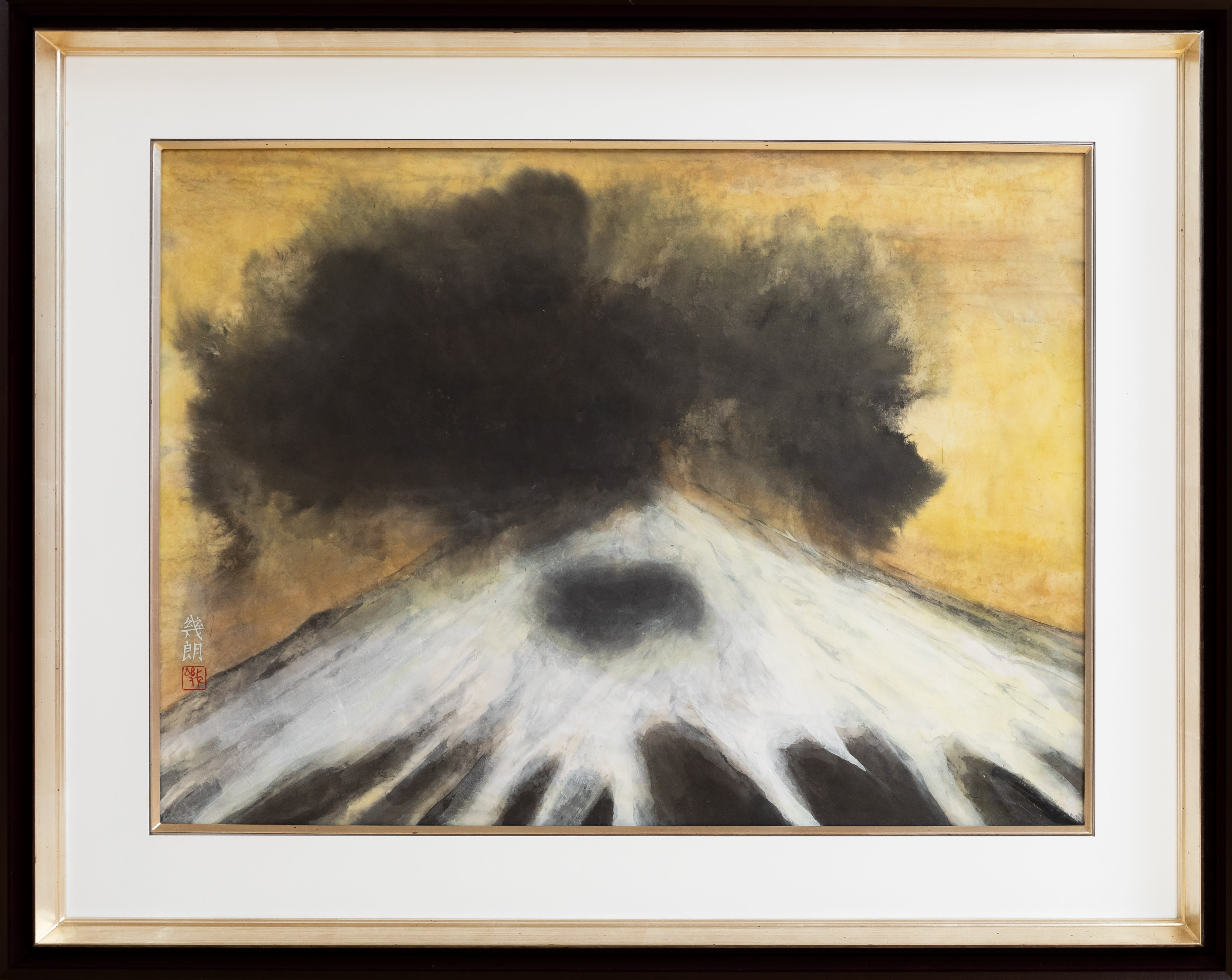

Q4: Yagi-sensei, please tell a story about your experience with the true nature of Mt. Fuji; why must you depict the mountain ‘from the front?’ (正面)。

Yagi:

I have climbed Mt. Fuji twice, but only up to the ninth station.

Fuji is not visible if you climb too high, so it is enough, but I can see it every day from near my studio. I was born and raised in Shizuoka Prefecture, where Mt. Fuji resides. Half of the days I can only see a hint of it due to clouds. I sketched the mountain about 100 times up to the fifth station, and even at the ninth station, but when the wind and rain suddenly turned violent we had to descend. Fuji is a beautiful cone-shaped dormant volcano that has erupted several times in the past.

When I climb Mt. Fuji, I feel God there. I am asked where I came from and who I am. Fuji is a mountain that I want to paint from the front, no matter what. It is a mountain that is not only scenic, but has true beauty.

Q5: Yagi-sensei’s first New York show focuses primarily on depictions of nature. Sensei, what do you want people to understand about your paintings, particularly those unfamiliar with suiboku-e or Nihonga?

Yagi:

Suiboku-ga is easy and difficult. I think that is why its history has been interrupted. It is deep and it is philosophical. If you do it seriously, you will not be able to draw good things, and if you do it seriously, you will not be able to stand up to it. I was told by my seniors that if I worked for about 50 years, I would be able to see something, but even now, I still can't, I don't know anything. What I do know is that I need to use a brush every day and look at the screen seriously.

Q6: Yagi-sensei, can you share with us your idea about carrying on the Japanese heritage into the future. In your case, it is traditional Japanese painting, “Nihonga", but please do not limit the fields on this subject. How have you approached and challenged this subject? Do you have any suggestions for the younger artists on this point?

Yagi:

I can't pass it on. I can't teach them. However, I can talk about the spirit.

To paint with your life on the line. To risk one's life to paint a picture that will give the people of the world a sense of emotional solidarity through beauty, and to wait for kind thoughts.

Ikuro Yagi's exhibition is Ippodo Gallery New York's final show at our Upper East Side location. In the new year, selected works from Yagi's previously unshown grand-scale paintings will be unveiled at Ippodo Gallery New York's flagship Tribeca gallery at 35 N. Moore Street.