Celadon is a term for pottery glazed in a jade green color, greenware. Other characteristics are a transparent glaze, often with small cracks used on stoneware and porcelains.

Ancient artifacts from as early as the Shang dynasty were found with this glaze. The Northern Song dynasty can also support that kilns in Longquan, Zhejiang province, China, mastered celadon glazes. Archaeologists have discovered shards with celadon ceramic glazes dating back to the Three Kingdoms. While the earliest primary type was Yue ware, the best-known production is Yaozhou ware. These types were widely exported to the rest of East Asia and the Islamic world.

For many centuries, celadon wares were highly regarded by the Chinese Imperial court due to the similarity of the color to jade, which was once the most valuable material in China. This classic gem color is produced by firing a glaze or clay body with a bit of iron oxide at a high temperature in a reducing kiln. Various other chemicals alter the color completely. Too little iron oxide creates a blue color. Too much gives it an olive tone. Celadon glazes can be produced in a variety of colors, including white, grey, blue and yellow, depending on several factors:

1. the thickness of the applied glaze,

2. the type of clay to which it is applied,

3. the exact chemical makeup of the glaze,

4. the firing temperature

5. the degree of reduction in the kiln atmosphere and

6. the degree of opacity in the glaze.

True celadon requires a minimum 1,260 °C (2,300 °F) furnace temperature and a firing in a reducing atmosphere. Today celadon glaze refers to partially transparent glazes with tiny cracks in the glaze, with a wide variety of colors.

The Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese characters for greenware is seiji (青磁). It was introduced during the Song Dynasty (960–1270) in China and Korea. In Japan, greenware is considered the most diverse style of ceramic art in the modern era, which is also avoided mainly by potters because of the high loss rate of up to 80%. The ceramic material, kaolin, usually used for porcelain, is found all over China, whereas it is only found in Amakusa, Kyushu. This rarity, however, didn't stop the production of critically acclaimed glazes achieved in Japan.

The glaze with mixed subtle color gradations of icy, bluish-white is called seihakuji (青白磁) porcelain. Pieces typically produced are tea bowls, sake cups, plates, mizusashi water jars, censors, and boxes. One artist, however, has expanded into the area of sculpture and abstraction. Tsubusa Kato is working exclusively with clay from New Zealand. Random glaze reactions in the kiln and his formative process combine in complex ways to create his works of sharpness and tension inspired by the sharp jagged edges of blades. The rough surfaces serve to emphasize and accent the natural flaws in clay.

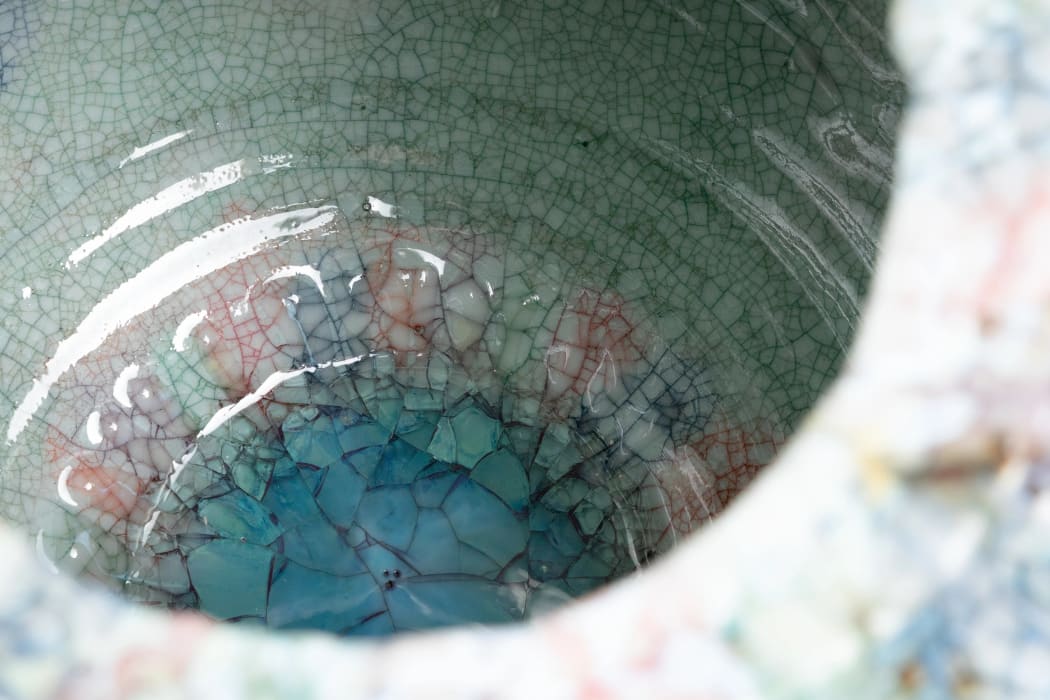

Here, the celadon glaze drips down the hand-carved bowl, highlighting the walls' uneven landscape. The opening is carved on an angel, which is the signature marking of Kato's work. As one peaks into the center of the bowl, one can see a thicker application of the glaze, creating a pool of serene celadon.

This delicate tea bowl, slightly askew, is decorated with an enso—the sacred symbol in Zen Buddhism, meaning circle or togetherness. The single stroke is painted on with the celadon glaze, and three drips appear in the center of the bowl. Notice the subtle hues of blacks and blues throughout the wheel-thrown bowl.

Takeshi Imaizumi originally studied traditional masterpieces from the Song Dynasty in China. His work combines Tenmoku and Celadon while experimenting with new glaze formulations and firing techniques to create his unique styles.

The subtle ombre effect of the purplish-brown top that ascends ever so lightly down the bowl's walls emphasizes the traditional cracking marks of a celadon glaze. The base contains drips and fingerprints of Imaizumi, which contrasts with the rich brown clay body.

Kodai Ujiie's Ofukei and Lacquer Sake Cup illustrates a harmony of accented colors amongst the mainly green body tea bowl. A thick layer of celadon moves alongside the face of the form, dragging the highly pigmented celadon oxide with it, creating bursts of watercolor-like finishes. The contrasting reds and contemporary kintsugi make a refreshing take on the traditional tea bowl.

The organic and grotesque lines and forms created, inspired by human layers of skin and flesh, are ever-present—rows of dripping red, green, blue, and purple lacquer drip down the bumpy surface. Combining Ujiie's unique kintsugi style and texture, warted like a gourd is an eye-catching work of art.