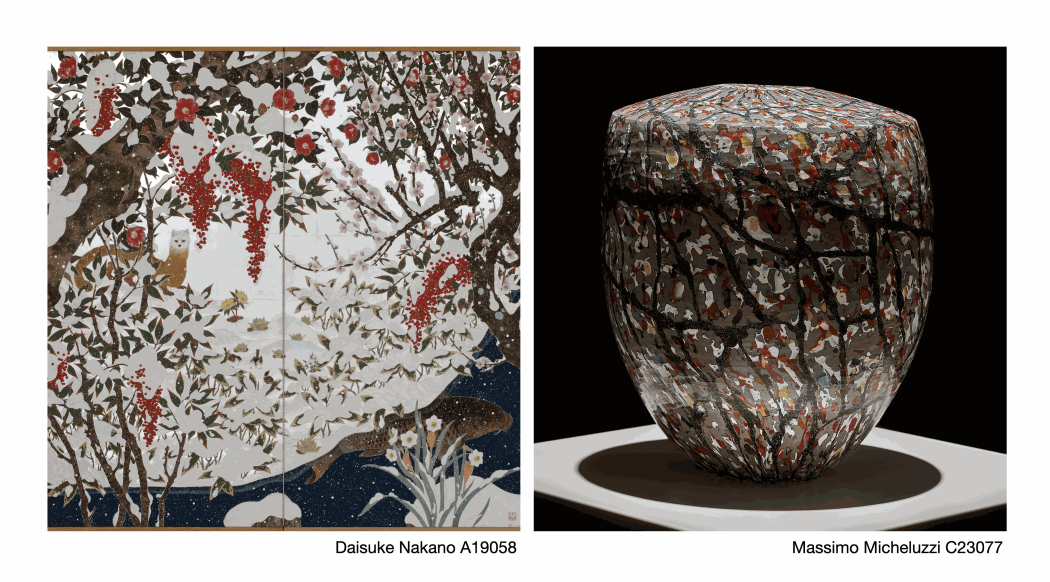

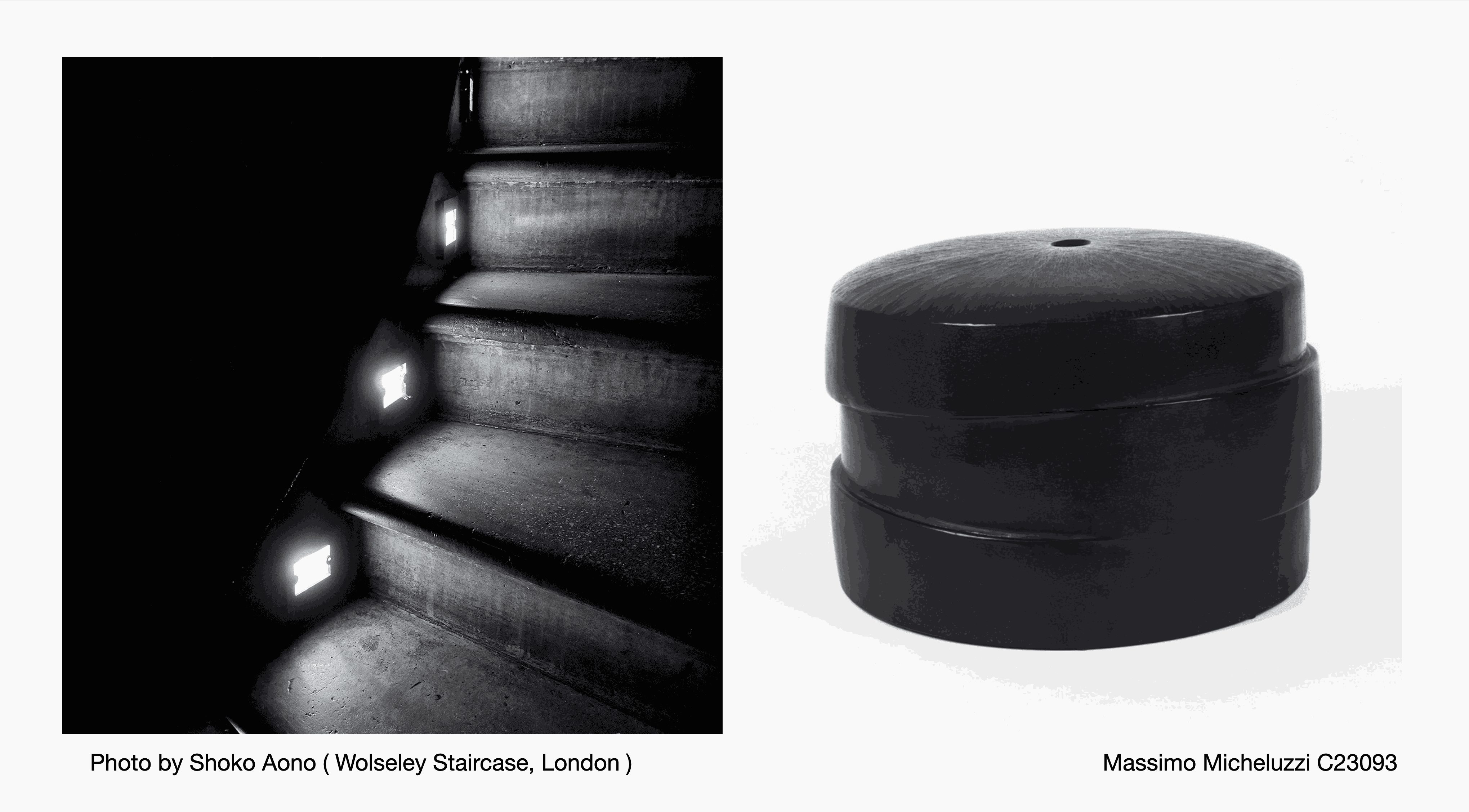

Massimo Micheluzzi, a Venetian artist at Ippodo Gallery, may seem like an unusual combination. However, Massimo's designs and patterns align with Japanese aesthetics or resemble traditional Japanese motifs. Explore our juxtaposition of Massimo's pieces with historically Japanese techniques.

In 1853, the United States forced Japan to trade. Commodore Matthew Perry stated: Agree to trade in peace or suffer the consequences in war. In early 1854, Perry returned to Japan with a fleet of nine ships, and the treaty of Kanagawa was signed. This treaty meant the end of Japan's 220-year-old policy of national seclusion. Japanese decorative art in the late Tokugawa (1603 – 1868) and early Meiji periods (1868 – 1912) was a time of enormous change. Global conflicts and internationalization mandated that Japan identify its specific features of culture and heritage through art and design.

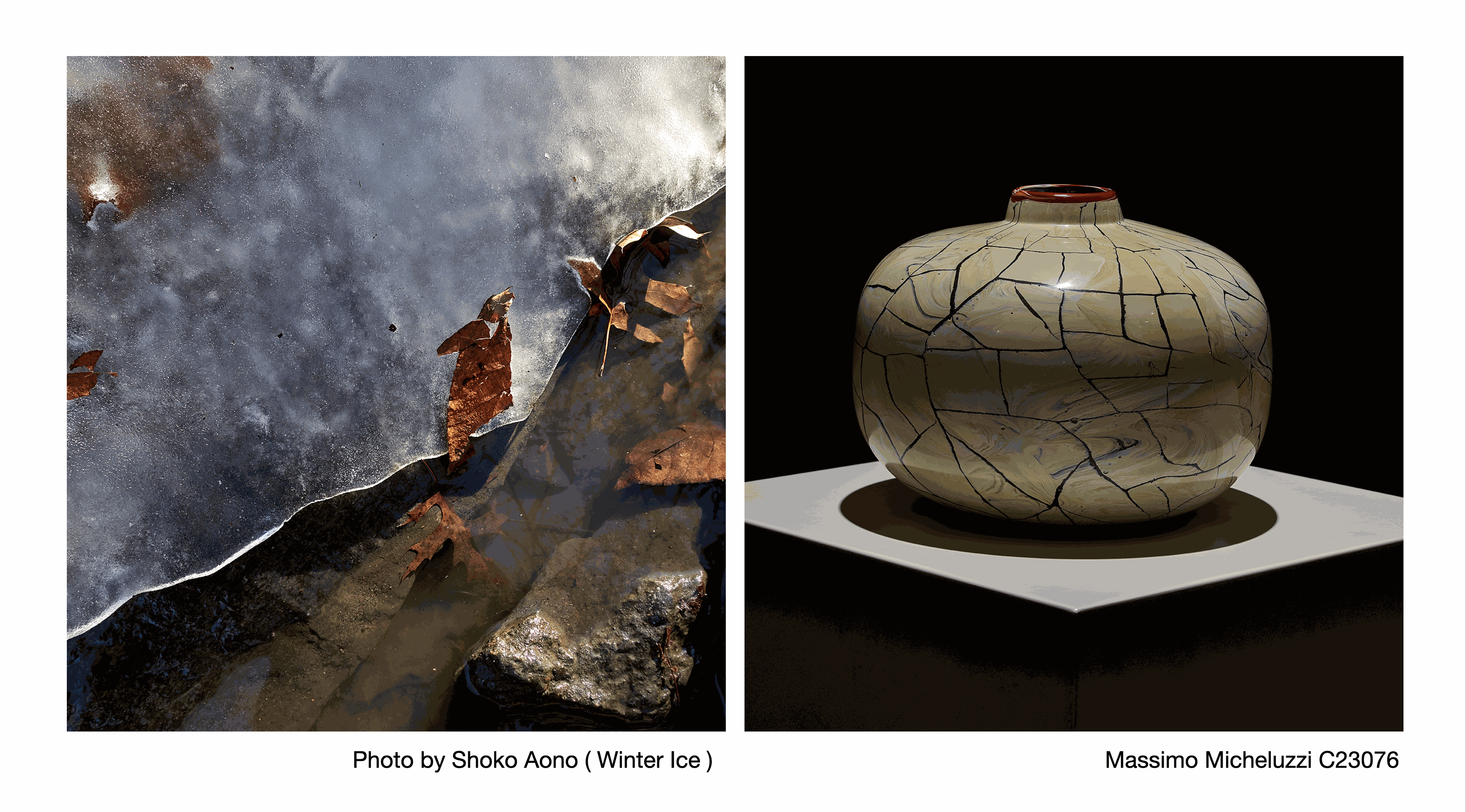

During the nineteenth century, the government promoted Japan's craftsmen at international industrial expositions. The international World's Fairs were an easy way to introduce Japan to the world and show off its crafts on a global platform. Crafts were specially created with intricate details to please European tastes and generate revenue for Japan. Artisans did not radically change their styles and techniques; it was the clientele that changed. International exhibition visitors were taken by Japan's artful wonders that had been closed off from the rest of the world. Japanese crafts became so popular that the most prominent non-Japanese artists fueled a new art movement called Japonisme. Japanese decorative art became famous not only because it was visually stimulating but also because it appealed to all the senses. The viewer is meant to hold the dishes, smell the food, read the poems, and imagine the crane's song and the sound of the wind blowing through the branches. This all-encompassing, multisensory-evoking art incorporated the idea of incompleteness (wabi-sabi), as well as tap into other ornamental styles. Wabi-Sabi is a rough and simplistic sensibility, which embraces imperfection. This artistic concept was applied to tea bowls in the fifteenth century. The black paint strokes show the skillful hand of Ogata Kenzan. Westerners were stimulated by the unique transcendence of natural beauty, which evoked the reverence of imperfection. By the 1880s, Japanese art and society smoothly moved between the old, new, Western, and Non-western ways of thinking. Artisans created designs and motifs for commoners for their aesthetic beauty and their symbolic resonance.

Massimo Micheluzzi's geometric mosaic piece is reminiscent of a Japanese design based on the bird's feathers on arrows. Since arrows only fly in one direction, newly wedded brides are gifted kimonos featuring this pattern for good luck so they wouldn't return home.

The West's fascination with lacquerware reinvigorated Japanese production but not it's quality. Traditionally, several artisans were involved in creating lacquerware. Our artists such as Tohru Mazusaki and Jihei Murase are master craftsman of lacquerware. They both employ the use of Vermillion red and lustrous black colors. It doesn't take much to the imagination that Micheluzzi's two red pieces in the gallery resemble lacquerware. This giant red, subtly decorated with other tones of red, looks delicate as a butterfly wing. Massimo Micheluzzi employs the Battuto Venetian technique that gives the vase another layer of dimension.

The Tōkaidō road, the "eastern sea route," became the main highway during the Edo period. Since the Tōkaidō road was relatively safe, the concept of travel for pleasure flourished. Pilgrimages to Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines became a leisure activity for every class. The fifty-three stations from Edo to Kyoto became popular due to artist Hiroshige's famous woodblock prints. Tourism became a common pastime as the information printed on guide books and woodblock print illustrations had a broad and rapid reach. These decorated pieces of paper created a vitality in Edo's leisure tourism (Fig. 17).

Micheluzzi's white piece with black cracks all over reminds me of a desert or the vast roads of trade that have been spread across the world. Here we see this piece juxtaposed with Shoko Aono's image of broken ice on a cold winter day.

Every culture shares a relationship between art and wealth. Decorative art is primarily funded by the elite class's wealth or "imperial capital." Through strife, turbulence, plagues, and natural disasters, decorative and applied arts are continually funded in all cultures. Over time, the increase in wealth among the merchant class transformed art forms that were once reserved for the court and elite military divisions. This group influenced the country's aesthetics by promoting fashionable textiles and employing artisans to make affordable objects for daily use by ordinary people.