A national and spiritual occasion, Oshōgatsu, the New Year, is Japan’s most significant holiday. Like the Chinese or Lunar New Year, Oshōgatsu was historically celebrated in late January or early February, but since 1873 has been celebrated on January 1st, when the Japanese government adopted the Gregorian calendar. Oshōgatsu represents not just the start of the calendar, but also a new cycle of the East Asian zodiac, with an accompanying animal that brings distinct energies and fortunes for the new year.

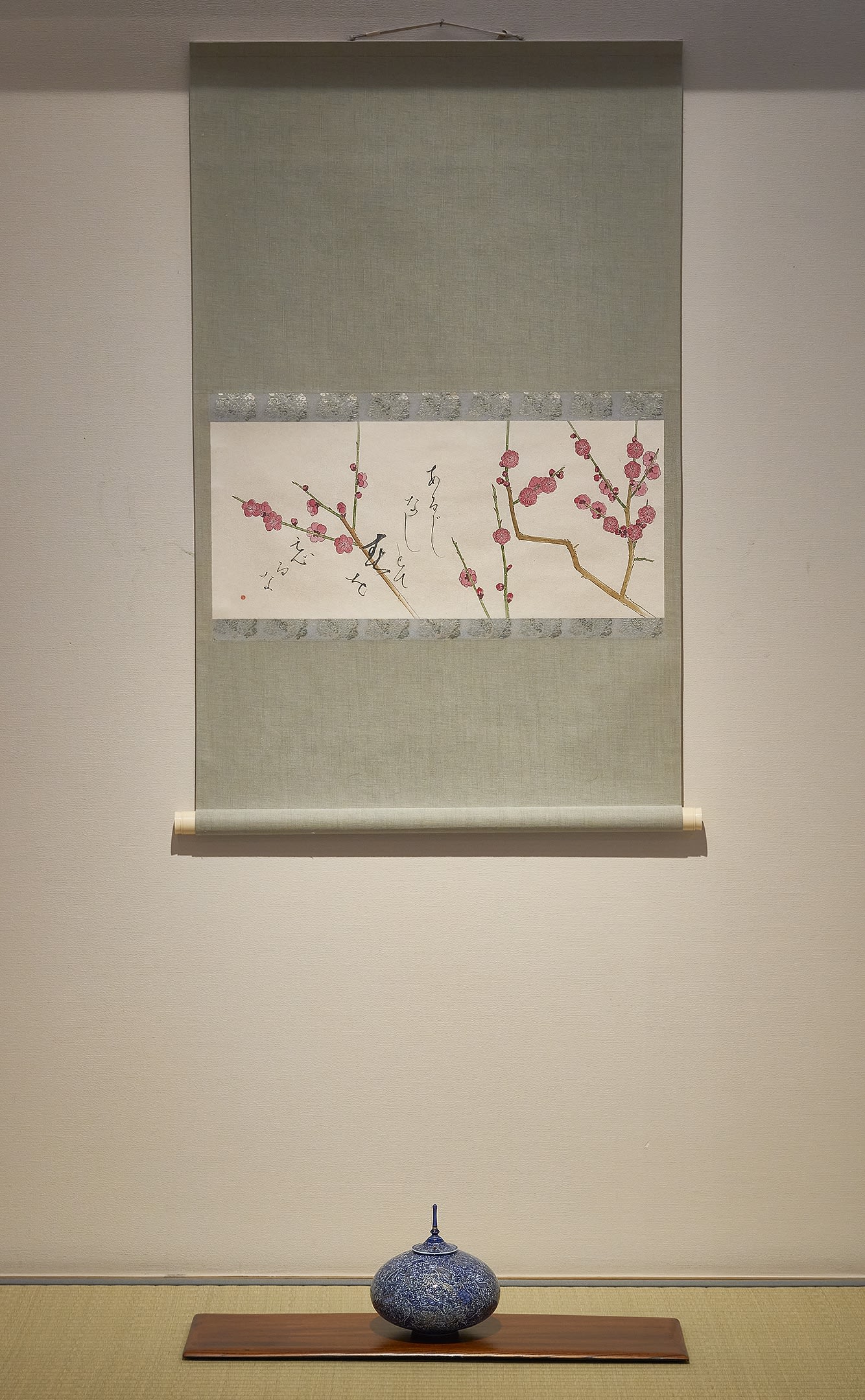

From December 29th to at least January 3rd, schools, shops, and businesses close as people participate in a range of rituals and gatherings to mark the beginning of a new cycle and invite good fortune. In the days leading up to the holiday, kadomatsu, or “pine gates,” arrangements of pine boughs, bamboo, and flowers are placed at the thresholds of temples, buildings, and homes, to welcome the arrival of Toshigami, the deity who presides over the new year. Gates and doors to homes are further decorated with shimekazari, wreaths made from straw rope, pine boughs, paper cutouts, which ward off bad fortune. Inside, in an alcove or on a family altar, people arrange kagami mochi, “mirror mochi,” a stack of two round rice cakes topped with a daidai orange (daidai sounds the same as the phrase “generation to generation,” signifying continuity), as an offering to deities who visit to celebrate the new year. People send cards to friends and family with good wishes for the coming year.

Around midnight on New Year's Eve, the still night is broken by deep tones of tolling brass bells, as many Buddhist temples strike their bells 108 times, a symbol of striving to overcome the Buddhist precept of the 108 earthly desires that bind people to the physical world. At neighborhood temples, adults and children line up for a turn to ring the bell and usher in the New Year.

On New Year's day, extended families gather at home to share food and spend time together. Children receive small gifts of money, otoshidama. At the center are osechi ryōri, traditional new year’s dishes, which are shared and enjoyed together. Prepared or purchased in advance in order to avoid cooking on New Year’s Day, osechi ryōri comprise a range of symbolic foods made from vegetables, egg, and seafood, typically preserved in vinegar and sugar and served in stacking lacquer boxes, or jūbako, usually with three or five layers. Special chopsticks, iwa-bashi (“celebration chopsticks), with narrow tips on both ends are used for the feast. The second, unused ends are said to be used by visiting deities.

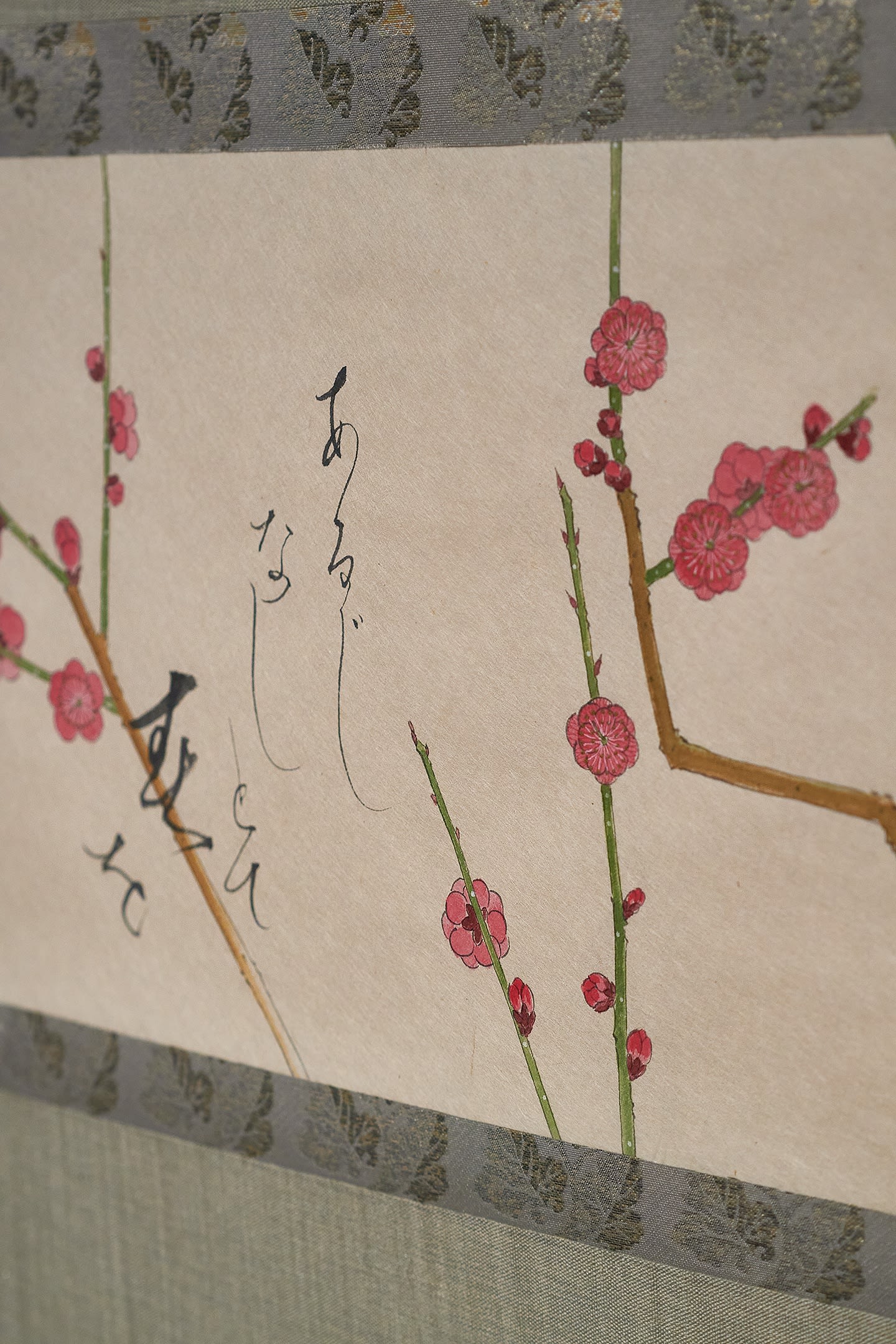

As people return to work and their daily routines following Oshōgatsu, friends and colleagues greet one another saying: “Akemashite omedetō gozaimasu, kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu.” (“Congratulations on opening the new year, please continue to look after me in the coming year.”)

As we approach the New Year of the Ox, we wish our friends and family good fortune, health, and relationships.

Contributed by: Harrison Schley