Suiboku-ga, or ink wash painting, is a style of monochrome, typically black painting that emphasizes nuanced brush strokes and uses diluted ink to achieve an infinite range of shades. Through ink wash painting, which was originally developed in China during the Tang dynasty (618–907), artists strive to create an image that captures the essence, rather than exact likeness, of their subjects.

The style was brought to Japan in the 14th century by Zen monks returning from China, where they had undertaken Buddhist training that included the practice of ink wash painting. These early Japanese ink wash paintings often reproduced Chinese themes, such as imagined Chinese landscapes. Later, even as Japanese artists incorporated native landscapes, portraiture, and floral imagery into their works, the genre continued to symbolize a connection between Japanese and Chinese cultures. Over the following centuries, as ink wash painting grew in popularity, it maintained a close connection with Zen Buddhism. During the Edo period (1615–1868), ink wash painting was often practiced in Sinophilic literati circles as an expression of mental discipline, literary refinement, and technical skill.

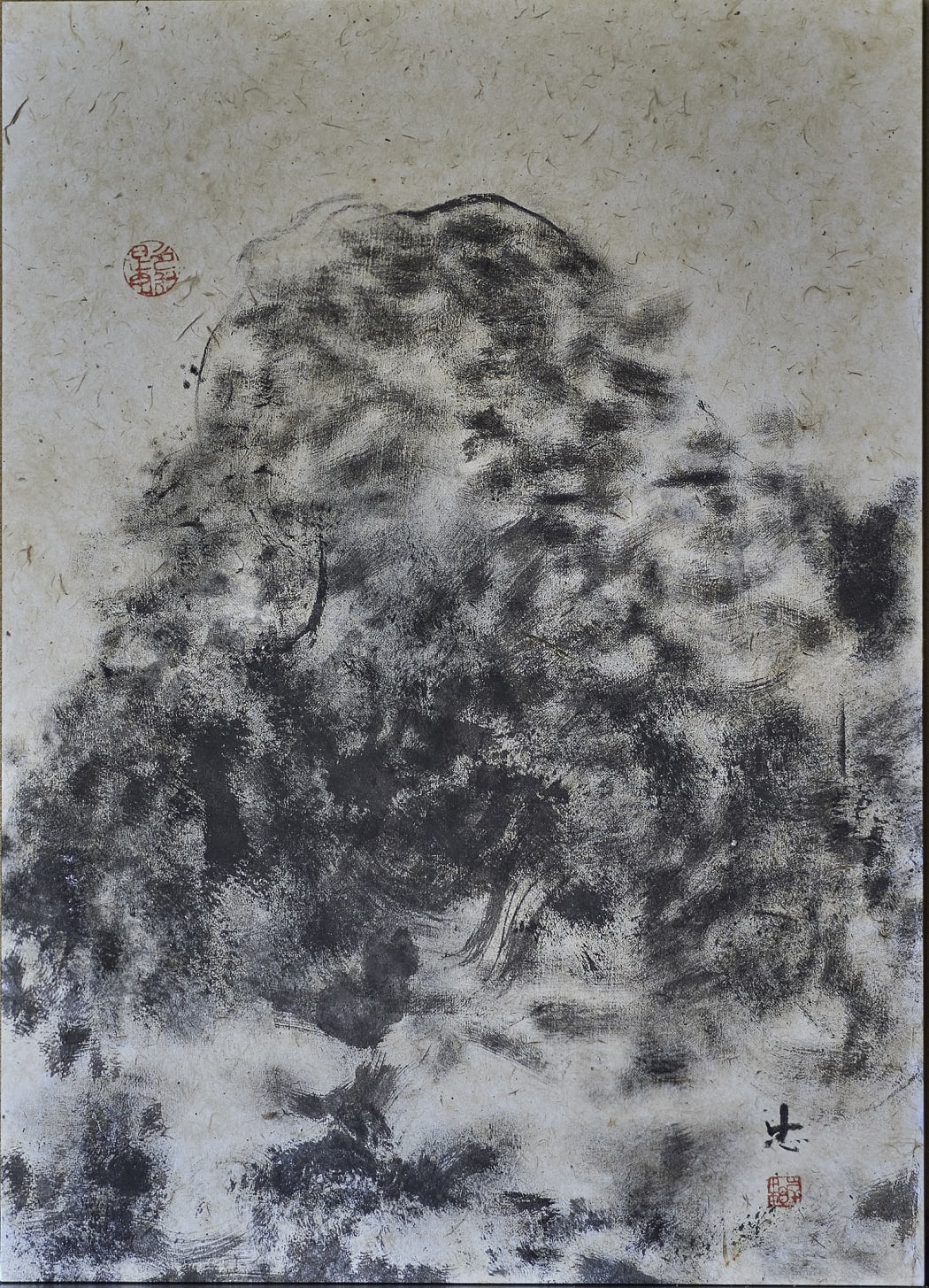

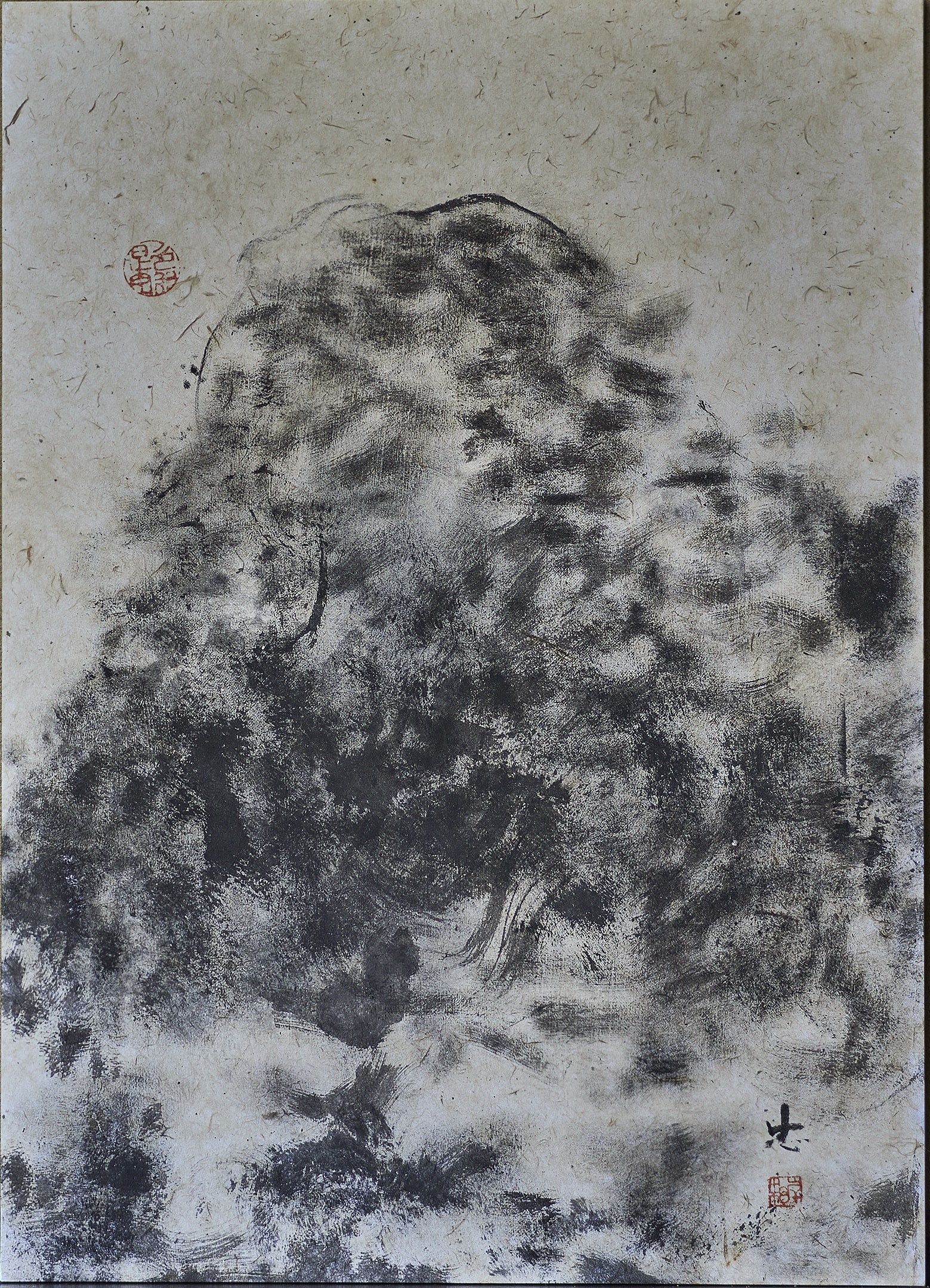

Samsara: Sculptures by Sho Kishino includes five ink wash paintings made by the artist’s father, Tadataka Kishino, a renowned practitioner of this style. Tadataka’s works are careful studies of space and nature. In Mountain, quick swirling brush strokes create windswept trees. A brush heavy with ink suggests branches laden with rain in Two Pine Trees. Typical of ink wash painting, Tadataka’s works focus on the drawn line and tonal value of the ink, using the empty space of the bare washi paper or silk canvas to suggest physical space such as the sky or a body of water. In his sculpture, Sho Kishino draws inspiration from this practice in a literal sense by incorporating the physical space that his works occupy into their composition.

Contributed by Harrison Schley